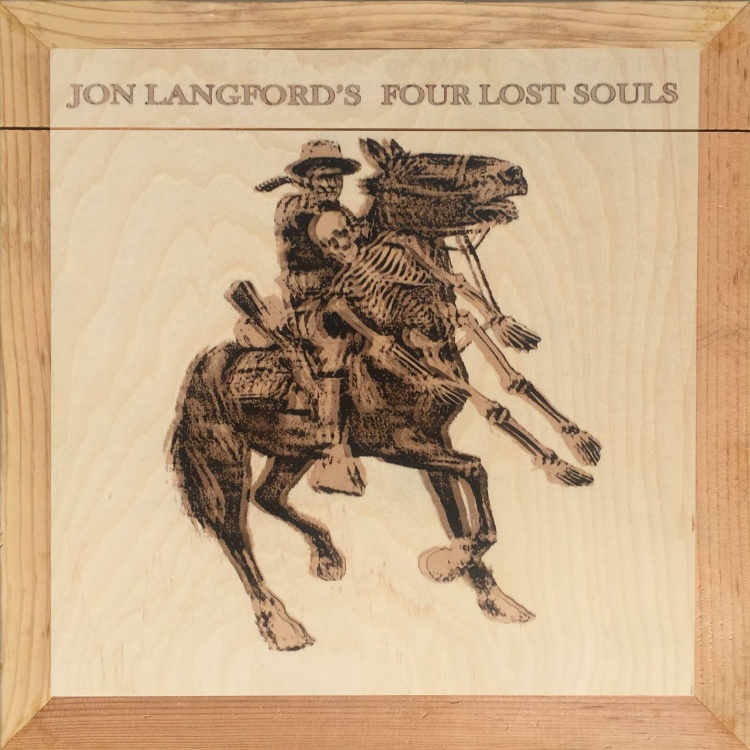

Jon Langford

Carted to Alabama under the cloud of dark politics, a band drew a glistening straight line from punk to country to soul to grand theater. On November 8th, the day after the 2016 election, Welsh-bred, Chicago-based musician and visual artist Jon Langford and a crew of merry-makers and alchemists filed into the NuttHouse studio, a one-story former bank building in Sheffield, Ala. (population 9,039). The musicians from Chicago, Nashville, Los Angeles, and just over the Tennessee River bridge made the pilgrimage to a place of legend and myth, where music runs as deep as the river’s current, to see what might come of it all.

Four Lost Souls, recorded over four days, originated in 2015, 100 miles north in Nashville where Langford produced artwork for Dylan, Cash, and the Nashville Cats: A New Music City, the long-running exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame. Fate had it that one of those Nashville Cats, bassist and producer Norbert Putnam, was so enamored with Langford’s paintings and piratey singing, he invited the stranger to come record in the Shoals.

A year later Langford is in that studio with many of the musicians who put the region, as well as renowned FAME Studios4 and Muscle Shoals Sound Studios5, on the musical map. Among them, members of the Swampers, David Hood6 and Randy McCormick—world famous players who have performed on all the songs you ever loved—and next-generation, in-the-right-pocket local drummer Justin Holder. Along for the ride were Nashville’s in-demand pedal steel guitarist Pete Finney and guitarist Grant Johnson. Together they dutifully crafted a project brimming with images of killing and hope, Faulkner, the Natchez Trace, and the sea.

As word got out around town, the musicians of the Shoals stopped by to see what Putnam was up to with these Chicagoans — Jon, guitarist John Szymanski, and the electrifying singers Bethany Thomas10 and now-LA-based Tawny Newsome. Tomi Lunsford, a mountain soprano from Nashville, slipped into the vocal booth to duet with Langford. The morning after his gig at Champy’s, a local watering hole, Will McFarlane parked his Harley at the front door to say hello. Five minutes later he was behind studio glass with his guitar. And five minutes after that, he was back on his bike turning the corner in a cloud of dust and exhaust.

Thus was the strange weather in the Shoals during that week in American history. Crammed between arrival and departure at the NuttHouse was a fever heat of creativity that crossed musical generations, racial lines, and the invisible barrier separating the flatlands of the upper Midwest and rolling hills of the deepest South. Even the ocean between the Delta and the dingy port city of Newport, South Wales, Jon’s hometown, evaporated out of sight.

The South is full of ghosts and they all ask unresolved questions. Nothing is settled and the music won’t sleep. Muscle Shoals itself personifies a place where America’s great cultural explosion transcends the murderous politics of race and class that stain this country from slavery and civil war to today. To tomorrow. The music speaks to the best in us, while reflecting, at times, the worst of us.

Four Lost Souls is pure Americana, not just because of where it was recorded or who played on what track, but because it is beyond the news of the day. It is a travelogue of sorts; it goes to a place where the differences between country, soul, blues, and rock-and-roll are blown aside by the warm languid breezes. The music had no time for such petty details, because in the moment, in that place, was the sound of sweet agreement.

Churchwood

Churchwood performs a vital and much-needed musical mission on their self-titled Saustex Records debut album: Saving the blues from the blahs and numerous other crimes and afflictions. Hailing from Austin, Texas, a city rightfully accused of being “The Boring White Blues Capital of the World,” the ingenious quintet kick the lazy butt of blues music into the second decade of the 21st Century and beyond.

And they do so with Bohemian panache, gonzo élan, punky ‘tude, bluesy grit and stunning musical mastery and imagination while keeping a firm rock’n’roll Vulcan death grip on the roots of the blues. The result is a sound that’s rife with the beef and the heart — if you get the drift — plus mind-expanded smarts and relentlessly wild and wooly soul.

The sonic scoop on Churchwood might best be expressed by a sampling of their song titles: The French symbolist poetics meets the rock’n’roll Burundi beat of “Rimbaud Diddley,” the mojo rising to a tempest of “Vendidi Fumar” (“I Sell Smoke”), and the soaring shredded shuffle of “Supermonisticgnositiphist

As guitarists Bill Anderson and Billysteve Korpi slash, slide, crunch and bend their six strings with lysergic abandon, drummer Julien Peterson and bassist Adam Kahan plow deep new grooves through the blues with twirling syncopation, and singer and harp player Joe Doerr wails, growls and howls like a mystic in the savage state. It’s synesthesia you can dance to, blues that’s refreshingly bereft of hoary bullpucky, and music that melds the heart, mind and crotch in an ecstatic orgy of sonic, melodic and linguistic adventurism.

The band has already inspired breathless raves in performance. “Though its members reside in Austin, wiry avant-blues collective Churchwood found its groove near the Dadaland exit off Highway 61,” notes writer Greg Beets in the Austin Chronicle. And as the San Antonio Express-News reports, “Austin’s dapper Churchwood played blues rock like a butcher knife: sharp and greasy with the potential to draw blood. Singer Joe Doerr had the fervor of a revival tent preacher, though he wasn’t necessarily working from the Good Book.”

Churchwood reunites Austin Music Hall of Fame guitarist and songwriter Bill Anderson and singer, harmonica maven, published poet and lyricist galore Joe Doerr after a 20 year break following their time in the legendary Texas bands Ballad Shambles and Hand Of Glory. In the interim, Anderson — hailed by the Austin Chronicle as a “whip-cracking badass” — played in such kaleidoscopically diverse bands as The Horsies, Joan of Arkansas, The Meat Purveyors and Cat Scientist while also working with such outsider musical artistes as Daniel Johnston, Neko Case and Jon Langford.

Meanwhile Doerr — who as famed rock critic Robert Christgau observes, “sings like he only masturbates twice a day because his boner makes it impossible for him to walk to his car” — finished his bachelors degree and earned a full ride scholarship doctorate from Notre Dame, published his first volume of modernist poetry, and now corrupts callow youth with the decadent magic of the language as a professor at Austin’s St. Edward’s University.

The latest collaboration from these longtime pals and partners in musical crime first slithered out of the primordial ooze when Anderson discovered the country-blues of Robert Johnson, Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt and Big Bill Broozy on old scratchy 12-inch long players at the local library during his high school years in Maryland. Landing in Austin in 1982, he worked as a roadie for the infamous Big Boys before signing on as a guitarist with seminal post-punk pioneers Poison 13.

Doerr arrived in the capital city of Texas a year later from St. Louis at age 21 “running away from trouble,” he quips. He joined up with his brother’s group The LeRoi Brothers to sing and wail the harp as Kid LeRoi for two albums of what Trouser Press describes as “solidly American music given a sweaty workout.”

The two then joined forces in the mid-‘80s in Ballad Shambles. Fittingly, the band made its live debut opening for the late Alex Chilton and released an EP on Skyclad Records. That group then morphed into Hand Of Glory, which Trouser Press hailed as “a diverse and exciting quartet. Mixing up cowboy rock, blues, Doorsy atmospherics and more with confidence and creativity, Hand of Glory is a strikingly potent band.” Issuing two albums on Skyclad, HOG has been rightfully accused of developing a sound that presaged what became known as grunge while a simmering Seattle scene only started to boil around the time the group broke up in 1991.

A few years ago Anderson found himself “on this Captain Beefheart trip where I listened to him all time, it made me want to play blues music again, but not the tired old one-four-five shuffle.” Doerr was of course once again his perfect vocal and lyrical foil.

Cat Scientist bassist Peterson made the switch to drums and followed Anderson into Churchwood, soon afterwards to be aided and abetted by bass player Kahan, who Anderson played with in the pit band for the play Speeding Motorcycle, a trippy dramatization of Daniel Johnston’s psyche. Korpi, veteran of such Austin bands as The Crack Pipes, Bloody Tears and Victims of Leisure, completed the lineup to add double guitar whammy in tandem with Anderson.

Creating a genuine band and music that was refreshingly original is the group’s raison d’etre. “Rather than just show how well we can play solos, I’d rather just create something all our own that no one else can do because we made it up,” asserts Anderson.

“What the other guys are doing musically is the same as what I am doing lyrically,” adds Doerr. “I’m just trying to say what nobody else has said.”

As Doerr puts it, “We are Churchwood, and we meant to do that.” Or as the Austin Chronicle advises, “This is one rabbit hole you won’t mind falling down.”